At Traverse Science, we pride ourselves on our ability to do systematic review 6x faster than businesses can handle internally. So what makes our process so much more efficient while maintaining the quality and precision that our clients rely on? We’ll be going into some of our methods in our new series: Optimizing your systematic review.

Data extraction is the single most time-consuming step in a systematic review.

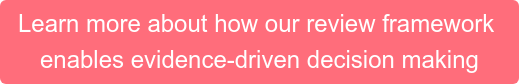

Even with only a single reviewer, extraction can easily take much of the time required to conduct the review. Throw in two (or more) reviewers, the person-hours required to complete extraction can easily balloon and blow your timeline (or your budget). So how do you decide on a review process that assures accuracy, while efficiently using your team’s time? We polled our followers on LinkedIn about their habits with systematic review: using a single reviewer, dual review with internal resolution, dual review with third party resolution, or crowdsourcing with three or more reviewers.

The results were really interesting:

- Most of our followers preferred dual review with resolution

- Second-most popular was dual review with conflict resolution from a third party

- A few suggest using crowdsourcing

- Using a single reviewer was unanimously avoided.

At Traverse, we prefer dual review with resolution for a number of reasons. But ultimately, we believe that having a consistent strategy is more important than the number of reviewers.

Why is a consistent strategy important?

Consistent strategy is the most important element of data extraction because it provides the framework that your reviewers use to do their work. Therefore, writing your extraction questions as clearly and specifically as possible leaves less room for individual interpretation and produces more reliable results.

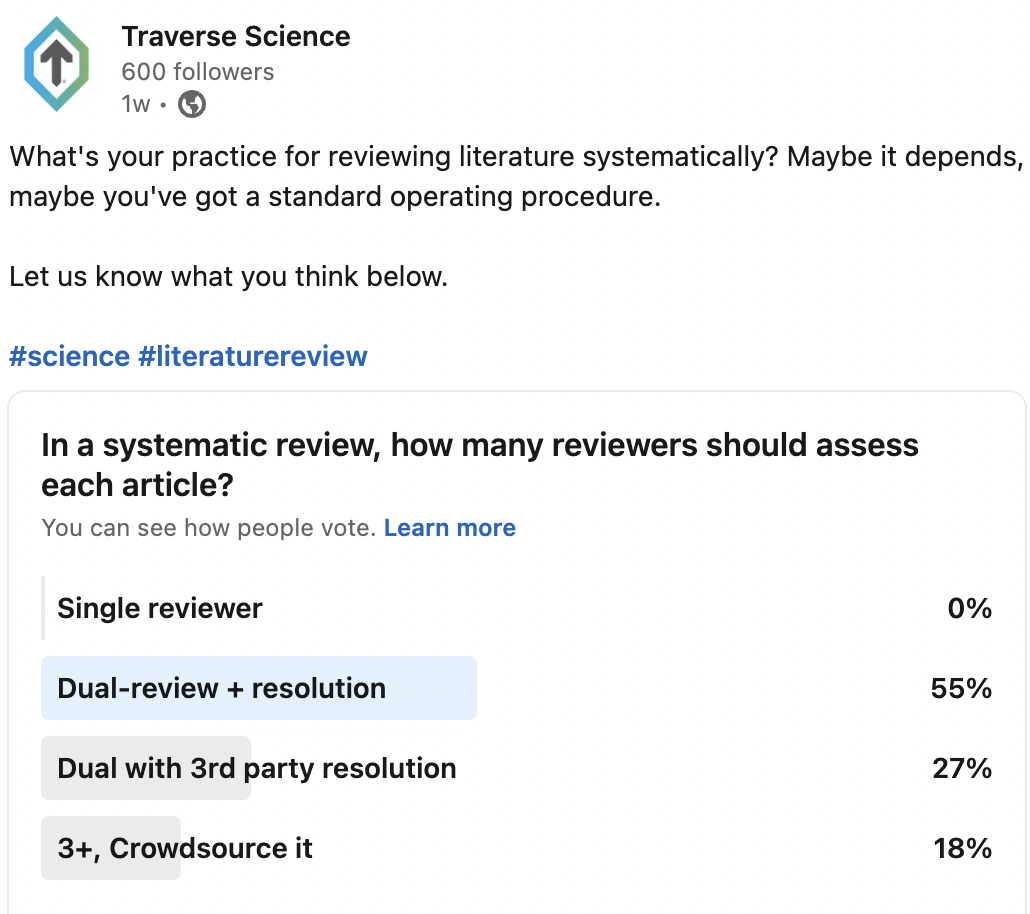

Let’s use sample size in this fictional review as an example:

The protocol says:

Sample size. Report the sample size of the study.

The text of the original publication says:

Methods. 500 subjects were screened for study inclusion. 50 subjects were randomized to groups A and B, each. 10 subjects were lost to follow-up.

The reviewer has been tasked with extracting sample size for the study. So, what is the sample size?

-

-

- 500

- 50

- 100

- 90

-

Depending on how you want to answer the question, all 4 are correct!

The problem ultimately boils down to two issues:

- Vague wording in the original prompt

- The review protocol the team is using

It is a clear example of how simple questions can be interpreted in multiple ways and shows that reproducibility is hard. However, some of this issue could have been avoided if the protocol specified that sample size is the total population at randomization, not just the size of the intervention group, and not the sample size at the end of the study.

So, which review method is right for you?

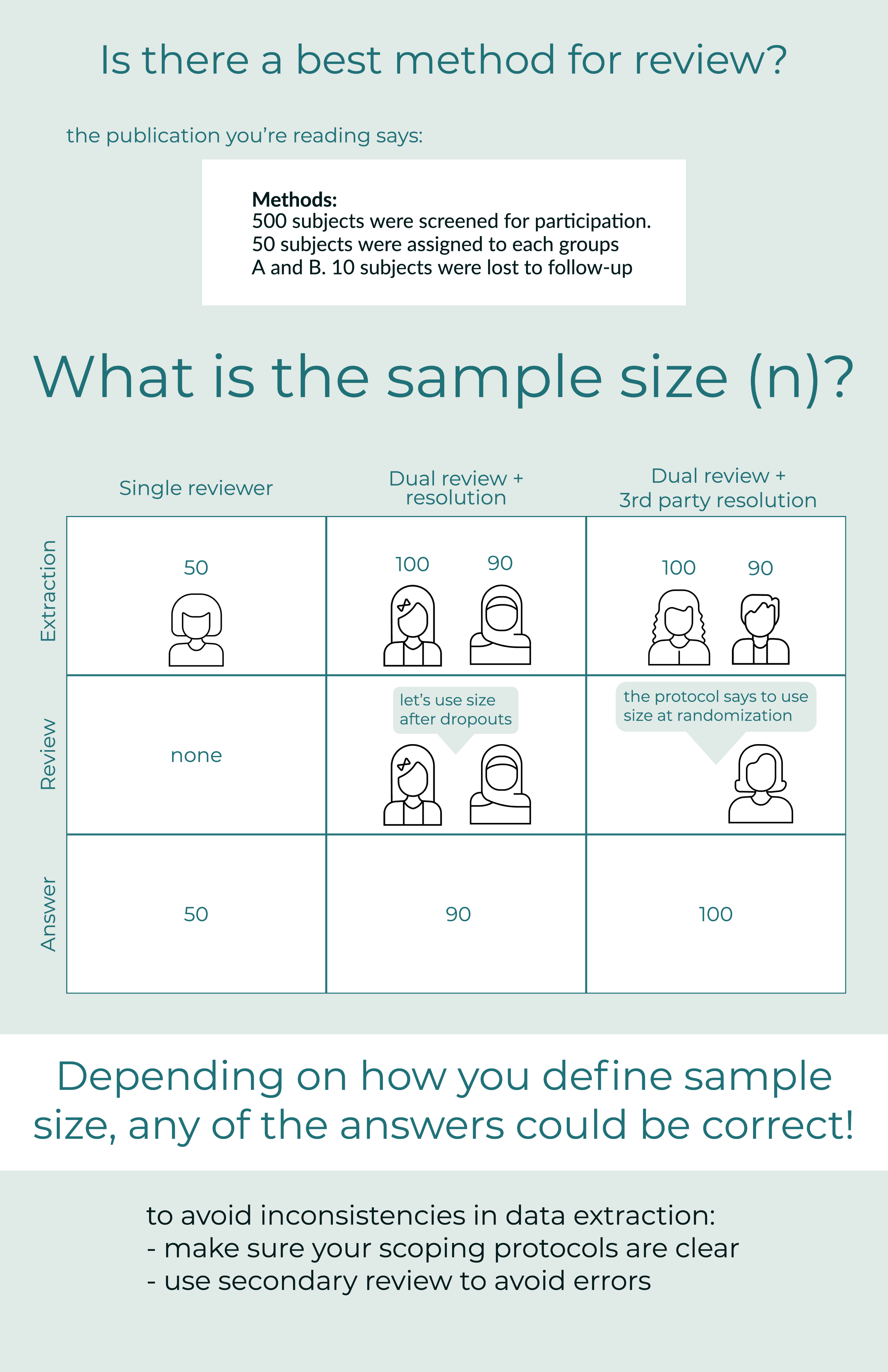

Single review

A single reviewer assesses the article, extracting data according to their needs/protocol.

Pros- Fast, easy, lean, the reviewer has complete control

Cons- Difficult to catch inaccuracies, prone to bias, low reproducibility

Even though no one chose single review in our poll, there are relevant use-cases for it. Examples include:

- Formulating an initial hypothesis

- Performing a rapid gap analysis to see where research is strong and where the holes are

- Strategizing research goals for your team

- Narrative reviews

- For better or worse, narrative reviews are free from the restraints of a systematic review. Here, a single reviewer (or team) could use elements of a systematic review like a protocol, but have each paper evaluated by a single expert.

In general, we don’t recommend single-review. Rare exceptions exist (such as when the reviewer is an expert in their field and reproducibility/accuracy aren’t issues) It is possible to bolster single review by having a single person extract the data and then have a second reviewer confirm their answers. In practice, we have found that the second reviewer tends to be biased by the first reviewer’s answer, confirming it quickly instead of closely following the protocol. Therefore, it is a less thorough option than dual review with conflict resolution.

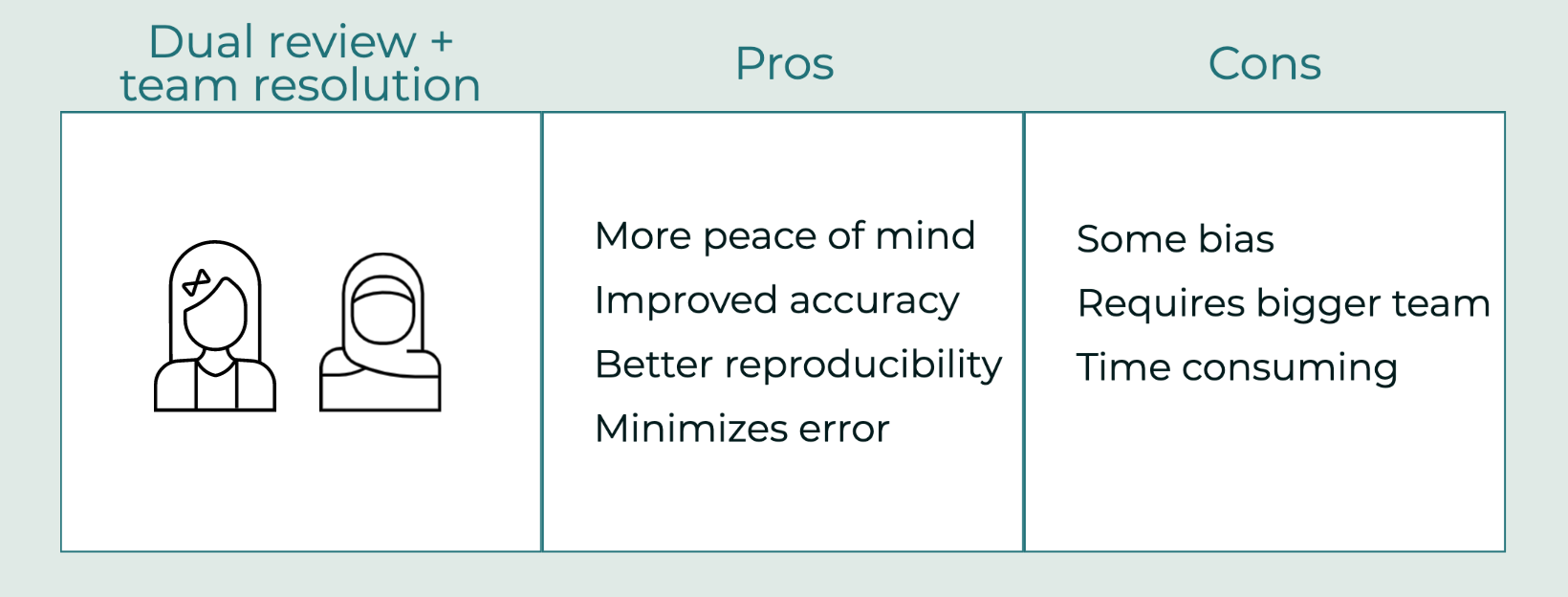

Dual review with conflict resolution

Here, each article is assessed by two independent reviewers in parallel. Where they disagree, they come to a resolution between themselves on the correct answer.

Pros- Increased peace of mind, improved accuracy, reproducible, minimizes error

Cons- Some bias, requires multiple people, time-consuming

Dual review with conflict resolution was the most popular option, and it’s also the most common method we use at Traverse Science. Since we’re a small team, we initially used single review, but quickly saw the benefits of dual review and pivoted to a dual review method.

Peace of mind

Knowing that your review was performed correctly gives peace of mind, which is perhaps the greatest value of dual review with conflict resolution. Many scientists know the super relatable, mostly unfounded dread that someday, someone will find every unintentional error they’ve ever made and call them out for the imposter they are. Dual review with conflict resolution helps mitigate that dread. You can rest easy, knowing that your review has been reproduced by a second person. And where it wasn’t reproduced, you took the correct steps to fix it, together. This one strategy will make a big improvement to the publication-readiness of a systematic review.

Labor intensity

Unfortunately, dual review with conflict resolution is time-consuming. There are some software solutions that may help streamline the process of identifying the errors and save time, but, even with the assistance of software, this is a laborious task. Usually, dual review with conflict resolution takes 2.5x the time of single review. Because dual review requires each party to take a second look at the paper, plus discussion to come to a consensus on the disagreement, the commitment can be intense. Sometimes the process of agreement is easy, but other times it reveals fundamental differences in the interpretation of a study’s reporting.

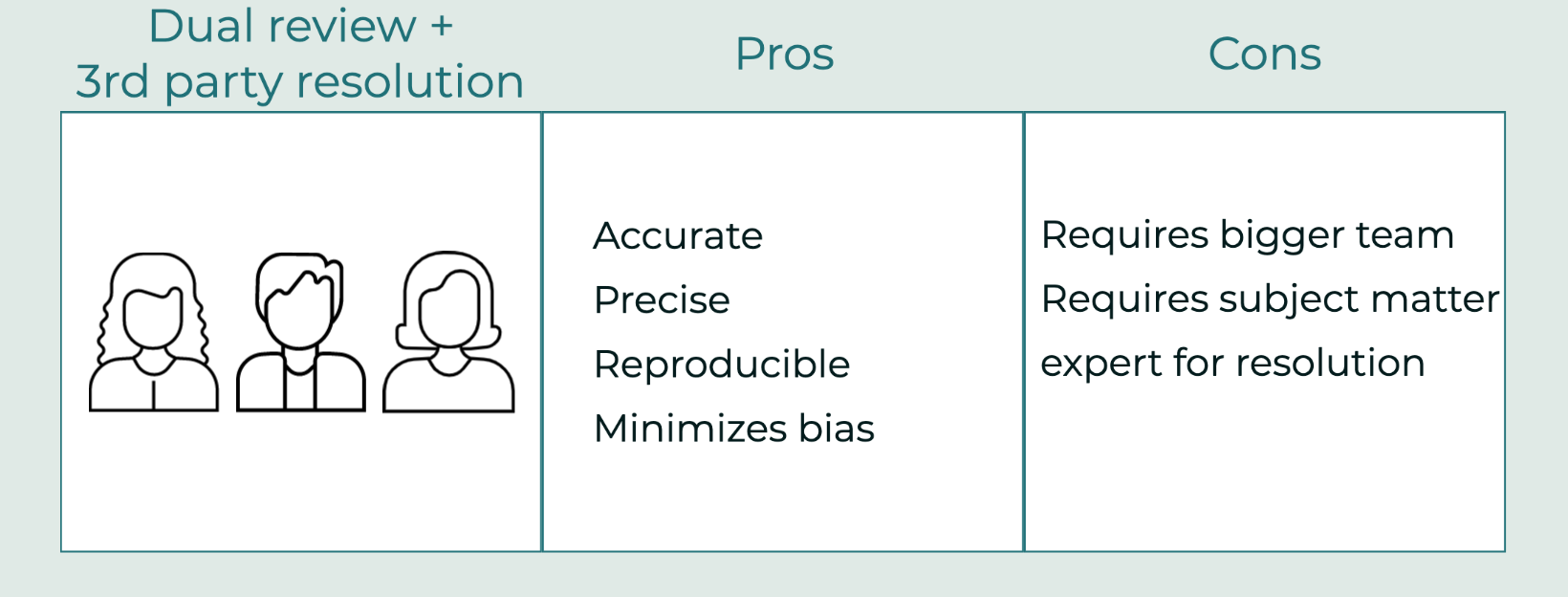

Dual review with 3rd party resolution

This is very similar to dual review with resolution mentioned above, except the conflicts are reviewed by a third party that did not conduct any of the initial data extraction. When done well, this option can lead to the highest quality, least biased data extraction.

Pros- Accurate, precise, reproducible, minimized bias

Cons- Minimum of 3 reviewers required, 3rd party should be a subject matter expert

Having a third party resolve conflicts between reviewers is only successful if the third party is very knowledgeable in both the subject matter and review protocol. We have found that when reviewers have completed their data extraction, they have become subject matter experts, intimately acquainted with the body of literature they have dove into. Thus, an independent third party can be a subject matter expert, come in to resolve conflicts, and be less knowledgeable on the body of literature than the initial reviewers. This makes them much less qualified to resolve conflicts related to the subject matter.

It can also lead to having too many different opinions on the topic, a classic example of “too many cooks in the kitchen”. To prevent this, it is imperative that the third party is very well-trained on the review protocol and has a solid background on the subject matter. At very the minimum, the third party should be well-versed in the review protocol so they can rely on a systematic decision-making process for handling conflicts.

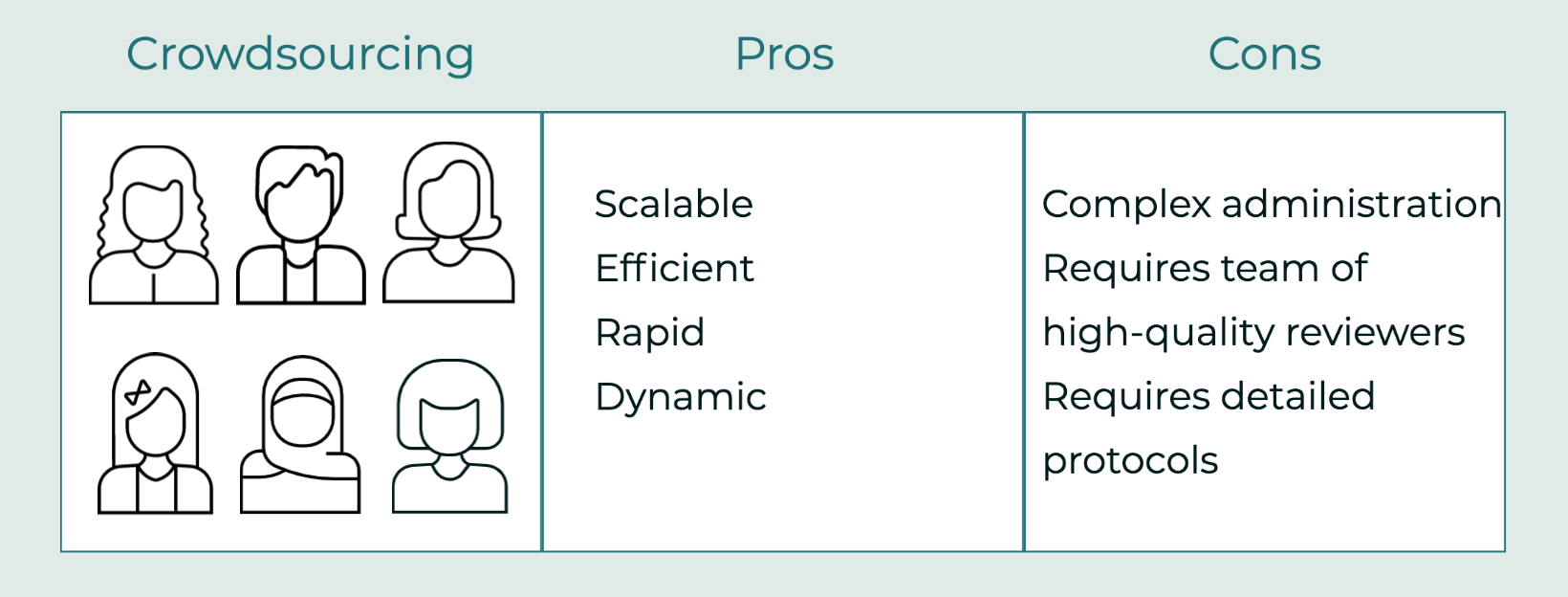

Crowdsourcing

Why limit your reviewers? Distribute the load by crowdsourcing your review. Set your number of reviewers per resource, extract data, and resolve disagreements in a distributed way

Pros– Scalable

Cons– Administratively complex

The crowdsourcing option of our poll was almost a joke, but it caught on a little bit! One of the big drawbacks of performing a systematic review is the time commitment – they can take so darn long! One approach to mitigate the time commitment that is crowdsourcing. Why have one, two, or even three reviewers? Why not ten? Fifty?

Unfortunately, we’re not aware of software that’s well-designed to handle crowdsourcing beyond dual/triple review. We also shudder at the thought of managing such an endeavor using Excel or Google Sheets. If you have a workable solution, please let us know!

Balancing the risks and benefits

While there are definite benefits to having more than one reviewer, there are also diminishing returns. If the risk of imprecision, errors, and bias is low, then having multiple reviewers does not add much value. But when small errors can result in big problems, having at least two sets of eyes on your project can pay big dividends! Either way, establish rigorous protocols, be consistent in your extraction, and reap the benefits of systematic review.